Love stories have been part of North Greenville’s history since its earliest days, when the school was still a small Baptist high school tucked into the foothills of South Carolina. Students met, courted, and sometimes pledged their futures beneath the campus trees or on the wooden swings scattered across the grounds. Among the first of those romances was the story of Vance “Vannie” Long James and Mays Milton Barnett—a partnership shaped by faith, learning, hardship, and extraordinary perseverance.

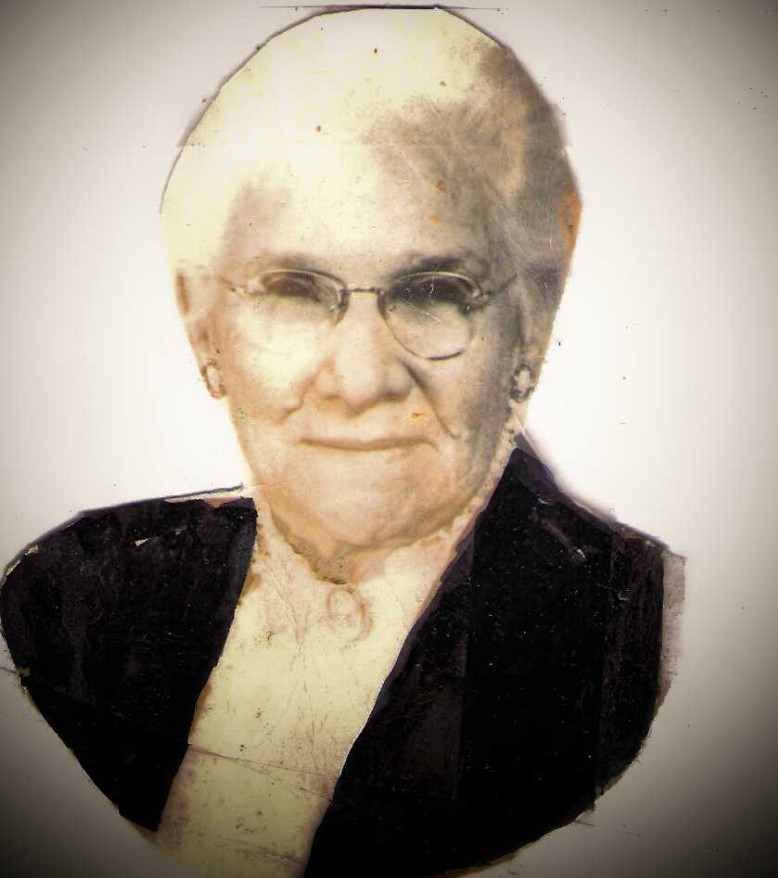

Vannie James was born on October 18, 1885, in Greenville, South Carolina, into circumstances far removed from those of her future husband. Her father, Zedic Westmoreland James, was a contractor and builder, and Vannie grew up in a relatively comfortable, even privileged, household for the era. Nearly three years later, on July 10, 1888, Mays Milton Barnett entered the world on Glassy Mountain, where his parents, Luther and Mary Jane Fowler Barnett, scratched out a living as farmers. One of twelve children, Mays learned early the value of hard work, responsibility, and faith.

Their paths converged at North Greenville Baptist Academy during the 1912–1913 school year. Mays was a senior; Vannie, a junior. Both quickly distinguished themselves as leaders in student life and scholarship. Together, they helped bring to life the school’s first yearbook, The Enlighteneer, published in 1913. Mays served as editor, while Vannie managed advertising—an early sign of the partnership that would define their lives.

Vannie was everywhere on campus. She led the E.Q.V. Literary Society, presided over the Philathea class, played on the tennis team, and belonged to the Midnight Club. In the yearbook, she listed her ambition simply: “to make others happy.” Her classmates seemed to agree, voting her the school’s “best all-around female.” Mays, meanwhile, was no less active. He served as senior class poet, president of the Baptist Young People’s Union, vice president of the A.C.H. Literary Society, and chief counselor of the Royal Ambassadors. During his time at North Greenville, he was even ordained into the ministry.

The yearbook staff captured Mays with affectionate humor, describing him as a “Jack of all trades,” a young man with “a number of irons in the fire,” equally willing to wash dishes, plow fields, fix pumps—or preach a sermon. It concluded with a playful rumor that he was “steering his ship to the sea of matrimony.” The rumor proved true. Shortly after his graduation, Mays married Vannie on June 22, 1913. That fall, he became the first in his family to attend college, enrolling at Furman University.

The Barnetts’ early married life was busy and full. Their first child, James Long Barnett, was born in 1914, followed by seven more children over the years. Joy was tempered by hardship when their second son, Mays Milton Barnett, Jr., developed hydrocephalus as an infant, leaving him severely disabled. Still, the family pressed forward, living in the Greenville area while Mays completed his bachelor’s degree at Furman in 1917.

Education and ministry shaped Mays’s professional life. He began teaching during the 1917–1918 school year as principal of Gowensville, and over the next decade led several Baptist academies across the South, including schools in Alabama, Virginia, and Tennessee. Wherever he went, he also pastored local churches. Eventually, he served as both pastor and head of the Bible department at the Haywood Institute in North Carolina.

In 1927, Mays accepted the call to become the full-time pastor of Riverside Baptist Church in Greenville County. Five years later, tragedy struck. In 1932, at just 43 years old, Mays died of stomach cancer, leaving Vannie a widow with eight children—all under the age of eighteen—during the depths of the Great Depression. With no income and no home of her own, the family was forced to leave the church parsonage where they had been living.

What followed might have broken many, but Vannie endured. Through the efforts of the Greenville Baptist Association, arrangements were made for the family to move to Connie Maxwell Children’s Home. Space was scarce, and funds were tight, but room was found in Memorial Home, a large, three-story house built in 1893 and reopened specifically to shelter the Barnetts.

Vannie lived in Memorial Home for twenty-five years. As her own children grew up and left, she became a house mother to generations of orphaned boys, sometimes caring for as many as twenty at once. Over time, she helped raise more than 100 children. Life had taught her discipline, resilience, and compassion, and she ran her household with firm expectations and deep care. Those who lived under her roof remembered her insistence on doing things well—laundry included—but also her unwavering commitment to the children in her care.

The Barnett family’s legacy of service extended into the next generation. Four sons—James, Dean, Luther, and Lee—served in the U.S. military during World War II, fighting across Europe, Asia, and the Pacific. All returned home, though not without lasting wounds. Two bore permanent injuries that shaped the rest of their lives.

Vannie died on January 26, 1966, at the age of 80. She was laid to rest beside Mays in the cemetery at Gowensville First Baptist Church. Their shared gravestone bears a simple, fitting epitaph: “Thy trials ended, thy rest won.”

Despite poverty, war, and loss, Vannie and Mays remained steadfast believers in the power of education. At a time when fewer than six percent of American adults held college degrees, all five of their able-bodied children completed college—four at Furman University and one at Winthrop College. Their influence extended far beyond their own family. One orphan Vannie raised later endowed a scholarship in her name at The Citadel, and another scholarship honoring Mays M. Barnett continues to be awarded annually at Furman University.

Together, Vannie and Mays Barnett left behind more than a love story rooted at North Greenville. They left a legacy of faith, learning, and lives quietly—but profoundly—changed.

Leave a comment